SAVING STARLIGHT

Northern Lights over Silver Creek Pond at Shades State Park

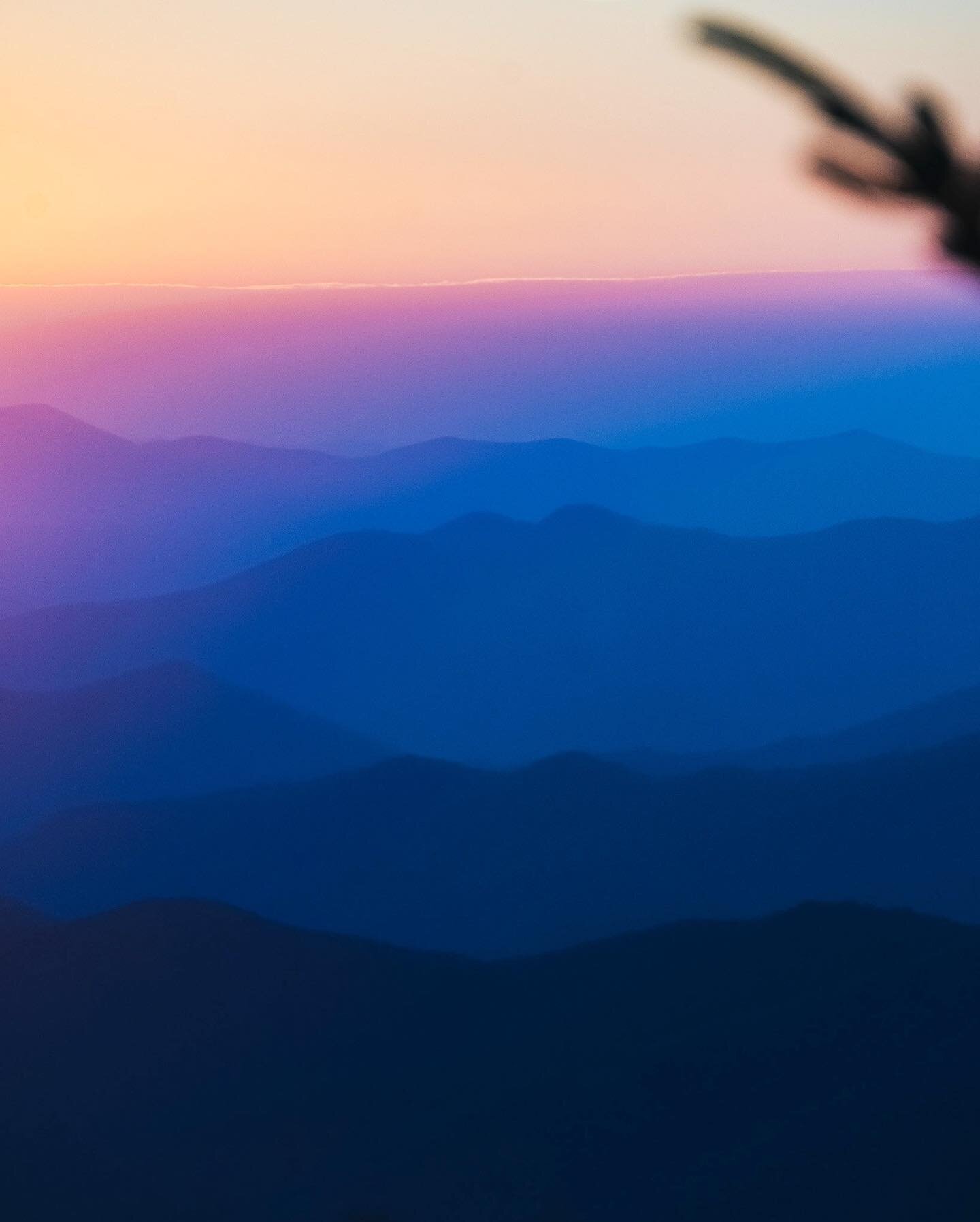

Nestled along Sugar Creek in northern Indiana, Shades State Park is known for its rugged ravines and scenic overlooks, shaped by glacial meltwater over thousands of years. The landscape here is rugged —layered sandstone cliffs cradle the narrow creek below, and thick forests press in on winding trails. At night, the darkness settles deep, untouched by city lights, wrapping around the land like an old, familiar blanket.

My girlfriend Claire and I camped there in May, looking forward to a weekend beneath its famously dark skies.

I recently read Johan Eklöf’s The Darkness Manifesto, which heightened my awareness of how artificial light reshapes the natural world. With the book’s message fresh in my mind, I was eager to experience the night sky in its truest form. Our timing turned out to be incredible; without realizing it, we arrived just as an intense surge of electromagnetic activity brought Indiana's most vivid Northern Lights display in over two decades.

The air was cool, and the sky unfurled above us in shifting waves of green and violet, pulsating in eerie silence. The trees stood as dark silhouettes, watching alongside us as the aurora flickered across the heavens. The moment, combined with what I had learned from The Darkness Manifesto, left me questioning how light pollution has altered the environment and our relationship with the night. This led me to explore its effects further, looking into how artificial light disrupts ecosystems and affects those who call Indiana home.

The Urban Glow

As night falls in Bloomington, a bustling college town in southern Indiana, streetlights flicker, casting light over quiet neighborhoods and the busy Indiana University campus. Farther north, Indianapolis brightens with glowing billboards competing for attention. The city hums, never truly resting. What was once a vast canvas of stars has faded, leaving only the brightest constellations visible while disrupting the balance of Indiana’s nocturnal ecosystem.

Artificial light, while necessary for safety and city life, lures insects from their natural surroundings. Known as “The Vacuum Cleaner Effect,” this phenomenon pulls moths, beetles, and other nocturnal insects toward artificial sources, keeping them trapped in illuminated zones rather than their intended environments. It’s like a nightclub with no exit—except the DJ is a fluorescent light, and the bouncer is a hungry bat.

For the creatures caught in the glow, this isn’t just a minor inconvenience—it’s a slow-motion catastrophe. Their instincts betray them, drawing them toward danger, much like hikers who ignore weather warnings and venture into the mountains unprepared.

The Essential Role of Moths

Milky Way on display at Negwegon State Park in Michigan

Among the insects drawn to artificial light, moths stand out for their ecological importance. While often overshadowed by butterflies, moths pollinate various plants that bloom exclusively at night. In Indiana, these include evening primrose (Oenothera biennis), wild petunia (Ruellia humilis), and yucca (Yucca filamentosa), which relies entirely on the yucca moth for reproduction. Moths also pollinate important crops such as soybeans, pumpkins, apples, pears, alfalfa, and grapes.

Fiona Matthews, Professor of Environmental Biology at the University of Sussex, points out that “moths pollinate flowers at a faster rate than day-flying insects.” That’s right—moths are basically the workaholic overachievers of the pollination world, yet they get no credit.

A 2017 study by German entomologists observed a 75% decline in insect populations over 27 years. This study is significant as it was one of the first to empirically demonstrate severe declines in insect populations in temperate regions, sparking widespread concern from scientists and the public alike. The implications are far-reaching, impacting plant pollination, nutrient cycling, and the availability of insects as food sources for predators. One of these predators is the bat, a mammal commonly associated with the night.

Consequences for Bat Populations

Each evening, as darkness settles over Indiana, bats emerge to hunt. Often misunderstood, these creatures play an essential role in balancing ecosystems and agriculture. The endangered Indiana bat, for instance, consumes large numbers of insects, reducing the need for chemical pesticides. Scott Haulton, a Forestry Wildlife Specialist for Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources, estimates that bats save farmers around $900 million annually by preventing crop damage. That’s a lot of money, yet bats still have a worse PR team than cockroaches.

Beyond pest control, bats contribute to the overall health of Indiana's forests and fields. Yet light pollution disrupts their routines, interfering with their ability to find food, locate mates, and migrate effectively. It’s like being at a party where someone keeps flipping the lights on and off—you’re just trying to have a good time, but suddenly, you can’t find your friends, and everything feels aggressively disorienting.

Losing these natural instincts is part of a more significant change—where we struggle to find our way in an environment dominated by artificial light.

Dimming the Cosmic Connection

Staring into the cosmos at Ka’ena Point

I lay in the sand at Ka’ena Point, the northernmost and westernmost tip of Oahu, Hawaii. The crash of waves fills the air as I stare upward, experiencing the night sky in its brilliance. This park, protected as an albatross sanctuary, is the darkest place on the island, far removed from the bright lights of Waikiki. The cliffs loom behind me, jagged and weather-worn, and the ocean stretches endlessly, meeting the sky in an imperceptible blur, its surface shifting gently under the horizon.

I visited many times during my three years living in Hawaii, but on this night, the moon's absence revealed an expanse of stars, unlike anything I had seen before. Overwhelmed, I felt a deep sense of insignificance and wonder.

Perhaps one of the most profound losses brought about by light pollution is less tangible and more existential. Once a universal part of the human experience, the night sky has become obscured for much of the world’s population. The loss is not merely aesthetic. The stars have historically held immense cultural, navigational, and spiritual significance. They have inspired art, guided explorers across oceans, and helped farmers determine planting and harvesting seasons.

When you look up at the night sky, you see the universe as it was before you were born and as it will be after you die. It’s a connection to the cosmos that transcends generations. As Carl Sagan said, “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.” Yet, as cities expand and the night grows artificially brighter, this cosmic view becomes increasingly reserved for those who can venture far from urban centers.

Efforts to reclaim the night sky are gaining momentum worldwide. Dark Sky Reserves and Parks are being established, where lighting restrictions preserve the night's integrity. In Indiana, where the night once stretched endlessly overhead, there is a growing recognition of the need to dim the lights.

A Brighter Path Forward

Arches National Park in Arizona

Since 1958, Flagstaff, Arizona, has been working to protect dark skies. The city introduced some of the first outdoor lighting policies to preserve astronomical research at Lowell Observatory. Over time, these policies evolved, requiring fully shielded outdoor lighting that directs beams downward, minimizing skyglow.

Flagstaff’s approach earned it the title of the world's first International Dark Sky City, a recognition granted by the International Dark-Sky Association. The city continues to protect its nightscape through community involvement, education, and the use of energy-efficient lighting with reduced blue light emissions.

The city’s approach provides a model for others, suggesting that urban areas worldwide could benefit from similar strategies. For example, shielded, downward-directed lighting and warmer-hued LEDs could enhance nighttime visibility and contribute to energy efficiency.

Individually, combating light pollution starts with simple home adjustments like replacing harsh lights with shielded fixtures, using timers or motion sensors, and lamps with warmer tones. Beyond personal actions, advocacy plays a crucial role; participation in community discussions and support for dark sky legislation can drive broader change.

At this pivotal moment, where technological advances meet the need for ecological preservation, the night sky calls us to value and defend its natural beauty. By adopting thoughtful lighting practices and promoting community involvement, we can safeguard celestial views that connect us to the cosmos and preserve the delicate nocturnal ecosystem, which benefits the world. Protecting the night sky isn’t just about seeing the stars—it’s about preserving our place beneath them.

Sources

Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting. Catherine Rich & Travis Longcore (eds). 2006. Island Press. Pages 281-304.

Hallmann, C. A., Sorg, M., Jongejans, E., Siepel, H., Hofland, N., Schwan, H., ... & de Kroon, H. (2017). More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLOS ONE, 12(10), e0185809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185809

Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife. "Northern Long-Eared Bat and Other Forest Bats in Indiana." in.gov, https://www.in.gov/dnr/fish-and-wildlife/files/fo-Northern_LE_and_other_forest_bats.pdf. Accessed 7 June 2024.

"The shocking environmental impact of treating wastewater with ‘forever chemicals’." University of Sussex, 24 May 2023, https://www.sussex.ac.uk/broadcast/read/60568. Accessed 7 June 2024.